For the renewal of democracy: Politicians’ School– an experiment to support grassroots political leadership in Hungary

The School of Public Life is a grassroots civic education center in Budapest, dedicated to building a democratic and just Hungary. It has recently launched a new leadership program called “Politicians’ School” to train a new generation of progressive, value-driven leaders. Building on the School of Public Life’s decade of experience in civic education, it equips activists and aspiring politicians with the skills, vision, and community support needed to renew democracy in Hungary.

Author: Tessza Udvarhelyi

download this article

Authoritarianism and citizenship in Hungary

Over the past 15 years, Hungary has become increasingly authoritarian and repressive under the rule of Fidesz. Opposition voices are silenced, activists are targeted, and social movements are suppressed. The media is ruled by propaganda and the autonomy of local governments as well as the independence of courts are under serious attack. Racism, sexism, homophobia, and a general fear and hatred of the “other” are integral parts of the national government’s policies and practices.

There is widespread suspicion among people toward public life in general and politicians in particular, which is both fueled by and contributes to the endurance of the current authoritarian regime. Among other things, this has led to drastically lowered standards among politicians on both the government and opposition sides in terms of their motivation and skills as well as to a general lack of citizen control over democratic processes. In addition to the more recent repression by the party state, there is a deeply rooted inequity in political representation. Our mainstream politics continues a several-hundred-year-old tradition as it is dominated by middle and upper-middle class, middle-aged white men, leaving a huge part of the population excluded from real representation.

For a real democratic transition, a change of government is not enough – citizens must reclaim public life as our shared responsibility both through effectively organized advocacy and by producing a new generation of dedicated and authentic pro-democracy decision-makers. The reinvigoration of civil society and the re-democratization of politics are deeply intertwined. In this way, as both activists and politicians need support to overcome political and social challenges, citizenship education and political education need to be part of the same theory of change.

From training activists to training politicians

The School of Public Life was founded in 2014 in Budapest as a grassroots school for activists based on the belief that social change happens when underrepresented communities organize, advocate for their rights, and assert their voices toward those in power. We help citizens and community organizations build impactful and resilient initiatives through training in organizing and advocacy, strategic planning, participatory action research and the publication and distribution of educational materials. Over the years, our organization has become the primary center of citizenship and political education for progressive organizations and pro-democracy social movements in Hungary. We offer learning opportunities for people at all levels of civic and political engagement starting with interactive board games for those with little or no experience in activism through workshops in various practical areas for those already involved and advanced training in community organizing and critical pedagogy to high-level courses such as engaging in civil disobedience or running grassroots electoral campaigns. In this way, we can engage a wide variety of people in education about social justice activism and pro-democracy organizing.

As the crisis of Hungarian democracy has become deeper over the years, our team has concluded that to build a democratic future, we need to move beyond our focus on grassroots activists and start supporting people who are willing to work for democracy in institutional settings at the local and national levels. There is a limit to what social movements can achieve if there are no elected representatives who represent their values and interests.

Having realized the lack of support systems and learning opportunities for those who are ready to take the risk of becoming a progressive politician in an authoritarian regime, in 2024 we decided to expand our pedagogical work further into institutional politics by developing the Politicians’ School. This program is designed for people who come from civil society, activism or community organizing and want to take a step closer to the institutions of power by getting elected. Our goal is to contribute to the emergence of a new generation of pro-democracy, value-driven and community-based political leaders who are able to work together with civil society and local communities in their effort toward social justice.

The Politicians’ School

The Politicians’ School is a long-term immersive leadership training program for prospective and newly elected politicians. It is a school for political change, turning politics from a tool of oppression into a vehicle of cooperation, solidarity and democracy.

As with all leadership training programs, we started out by identifying the kind of leadership qualities our organization would like to foster in our trainees. We have built on the work of the Kairos Center that identified the key characteristics of effective leaders working for social change. According to their model, ideal leaders of social change must embody the four Cs. They need to be clear, competent, committed and connected. Civic and political leaders must have clarity as in being able to understand and analyze the social and political context and formulate a clear vision. They also have to be competent, as in having the necessary skills to organize teams and also be able to make policy. They have to be committed, as in dedicated to the cause of social justice and taking their role as leaders seriously. And finally, they have to be connected, as in consciously building community and being able to engage with a large network of people.

In line with the four Cs, the curriculum of the Politicians’ School covers a wide variety of topics from the development of personal qualities through practical skills to policymaking. Many elements of the training overlap with our pedagogical work with civil society organizations, as activists and politicians need many of the same skill set and tools. In addition, the sharing of skills across these boundaries contributes to improved mutual appreciation and cooperation between civil society and politics, which is essential for the rebuilding of democracy in Hungary.

As for the profile of potential trainees, the School is intended for people who have experience in community work, share our values of an inclusive democracy based on solidarity and participation and are either weighing the possibility of entering politics or have already been elected. An important aim of the program is to recruit members of underrepresented communities such as women, Roma Hungarians, people with disabilities and people with a foreign background. We want politicians who reflect who we are — diverse in gender, age, class and background, united by a commitment to democracy. When it comes to the recruitment and selection of participants, we also put an emphasis on age and geographical diversity by inviting both young and older people as well as people from bigger cities and smaller towns and villages.

The first pilot year

The pilot year of the Politicians’ School took place in 2025 over 6 months (with preparations starting in the fall of 2024 and follow-up happening in the fall of 2025). We recruited applicants by sharing a call for participation among social movement organizations and progressive political parties. We had about 50 applications for 15 spots, so we made two rounds of selection. First, we evaluated applicants based on their application forms, assessing if they align with the aims and values of the program. Then, we conducted personal interviews with applicants who fit our profile. We determined the final list of trainees by taking diversity and group dynamics into consideration.

Our first cohort started their training in January 2025 and included 18 trainees, most of whom were freshly elected representatives in local governments, while some were planning to run in the 2026 parliamentary elections. Most cohort members were based in Budapest, while one third of them came from smaller towns and villages. They all had different organizational backgrounds including community organizations and political parties and all of them wanted to play an active role in making Hungary a democratic country. In terms of age, the program members ranged from people in their early 20s to those in their 60s. More than half of the participants were women, and some of them belonged to minorities such as Roma Hungarians and people with disabilities.

Regarding methodology, the program included in-person and online training sessions, a personal project assignment, one-on-one mentoring by active politicians, a three-day study trip to Vienna, group coaching and community building activities.

The training sessions were mostly conducted in an interactive and iterative way to allow trainees to share experiences and learn from each other but also included some more traditional presentations and panel discussions. In-person training sessions involved activities that drew on the active cooperation of cohort members while online sessions were more about the transfer of knowledge such as information about policies. Our program members learned not only about how politics works, but also about how to remain true to their values while leading for social justice.

the arch of the training sessions addressed the following larger topics

What is our vision and mission?

- identifying the qualities of a democratic country

- identifying the qualities of a good politician

Where do we work?

- exploring the social-political background of trainees’ electoral districts

- research methods and tools of gathering information

Basic skills

- organizing a group

- building a social base

- strategic planning

- scenario planning

Basic knowledge

- how municipal and national governments work

- progressive policymaking in housing, education and mobility

Leadership skills

- how to be a good leader

- how to build a strong team

- how to remain true to our values

- ethical behavior in politics

- personal and team wellbeing

To ensure that trainees integrated what they learned during the program into their everyday work, cohort members were asked to come up with a practical project to complete during the program. These personal projects reflected our common learning experiences but were always specific to the work of each participant. To help program members find the focus of these projects, after each training session participants received specific assignments such as finding data in publicly available data sets, reading municipal and national strategies or designing a plan for activist recruitment. We also offered one-on-one consultation about these projects and all of the participants presented their projects to the whole group at the end of the program.

Mentoring by practicing politicians was a highly appreciated element of the program. Every participant was paired with a politician who is either practicing now or has extensive recent experience in politics. We put a lot of energy into finding the right partner for each participant and asked them to meet each other at least five times during the program. Most pairs met in person, but some decided to do the mentoring online. We provided discussion guides for the mentors and mentees to help them in their conversations. Feedback about this mentoring opportunity was overwhelmingly positive as trainees got to know the “real world” of politics through the experiences of people with shared values.

We offered group coaching in small groups three times during the program. The aim of these sessions was twofold. First, to familiarize trainees with the practice of coaching and emphasize the need for mental health support in politics. Second, we hoped that these sessions would allow cohort members to share and address personal challenges related to their political careers. This was the element of the program that received the most criticism as some program members did not feel comfortable with the format or did not resonate personally with the coach.

The three-day study visit abroad has several different aims in this program. One is to make the program attractive to prospective trainees as many Hungarians don’t often have an opportunity to go abroad. The second is to make participants familiar with best practices in progressive politics, policy and activism in a social context that is different but not too far away from our own. The third aim is to create a strong community-building experience. During our study visit in Vienna, we learned about the local political context, met local grassroots organizations and local elected representatives, visited a department in the local government and took part in a sightseeing tour of social housing among other things.

Community building sessions were not merely an afterthought in this program. We believe that community support is essential in any political setting, but especially crucial in an authoritarian regime, where being a progressive politician can be an isolating experience. Every in-person training session included a shared dinner, which was at times combined with the screening of a movie or other program. We watched Alcaldessa together, a documentary about the election of Barcelona’s municipalist mayor, Ada Colau. We also organized picnics and outdoor activities during the program.

The program does not end when educational activities of the specific cohort are over. Inspired by Local Progress in the US that provides leadership and policymaking support to progressive local politicians and their staff, we would like to build a long-term alumni community. Our aim is to continue supporting our students in their political career and help them build a long-term supportive network. So, at the end of the training program, we encouraged trainees to become the first active members of our alumni community, which will grow with subsequent cohorts. The programming of the alumni community is still in formation as it will be based on the needs and contexts of cohort members.

Feedback and evaluation

In order to make the most of our pilot year, we asked trainees to give feedback about each session and we also spent time evaluating each element of the program afterwards. In short, cohort members found the in-person training sessions, the one-on-one mentoring and the Vienna study trip the most useful and rewarding, while they appreciated the online sessions and the coaching less. Some program members also had difficulty completing their personal projects as they could not find topics suitable for both the training period and their political careers. They also expressed the need to spend more time with each other outside of the formal training sessions to support each other in the implementation of their personal projects.

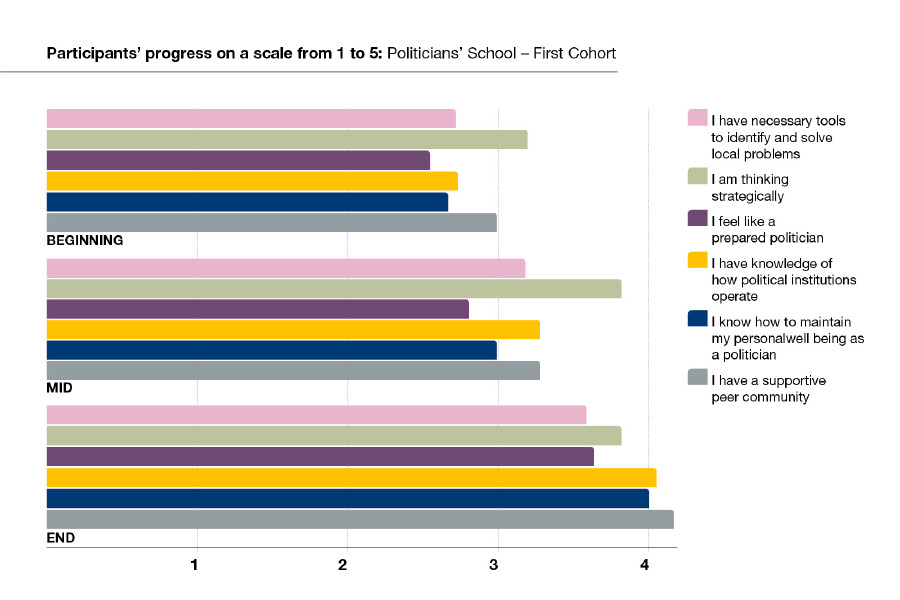

We also conducted a comprehensive impact assessment measuring trainees’ abilities, skills and confidence in certain areas in three phases: at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of the program. At each stage, cohort members evaluated their own development across a set of predefined indicators using a 5-point scale. This structured assessment allowed us to track progress over time and understand how the program contributed to their personal and professional growth. The indicators were defined based on the School’s objectives: identifying and solving local problems, using political institutions, enhancing knowledge about advocacy and community building and improving their self-confidence and well-being. The following graph shows the aggregate results of the group along the same variable at three points in time.

The results demonstrate clear and consistent improvement across all key indicators. Participants reported significant gains in their knowledge base about how institutions work and how they can use strategic thinking and other tools (evidence-based policy, group building, advocacy) acquired during the program. The upward trend observed between the initial and final assessments confirms the effectiveness of the training methods and the relevance of the program’s content. By the end of the program, cohort members reported greater confidence, stronger skills and a renewed belief in collective change.

Beyond quantitative results, trainees also highlighted the importance of the community and peer learning aspects, fostering collaboration and mutual support. Participants got to know each other’s local realities and learned to present, discuss, advise and debate ideas. This collective dimension added depth to their individual development journey, strengthened group cohesion and reinforced the program’s long-term impact.

Practical aspects

The Politicians’ School is a long, complex and expensive program that requires a well-prepared staff to be successful and effective. In the first pilot year, we needed two staff members to devote their full attention to the program for an entire year including preparation, recruitment, evaluation and follow-up with regular additional help from many other colleagues in the School of Public Life. Besides, inspired by the Better Politics Foundation’s (formerly Apolitical Foundation) Accelerator program for non-partisan Political Leadership Incubators (PLIs), we also created an advisory board of former and current politicians who gave us feedback and input regarding the whole program in general and the curriculum in particular and offered their network to find our mentors.

In addition to internal staffing and external expertise, the program also requires adequate financial resources. While our mentors and many invited guests joined the program for free, the program covered all expenses related to travel, accommodation and catering during training sessions as well as the whole Vienna study trip. The program was partly supported with the help of grants and partly through the financial contributions of trainees. While our trainings in the School of Public Life are always free, we made an exception with this program and asked cohort members for a symbolic fee to ensure their commitment and the program’s long-term sustainability. At the same time, to make it affordable to everyone, we offered program members the opportunity to ask for a discount or pay in instalments.

The road ahead

We identified several areas for improvement in the program that will be addressed in the next cohort in 2026. Among these is the integration of more content relating to national politics. In the 2025 cohort, content related to municipal governance was deeper, but with the national elections in 2026, this political arena will need a lot more attention. We also need to rethink the support provided for the planning and implementation of personal projects to make sure that this is not a burden but a tool of improvement for participants. We have also decided to replace coaching with small-group work for the next cohort where trainees can support each other directly with their projects. Regarding the study visit, we will keep improving the programming of the Vienna program while also exploring other neighboring countries such as Poland and Slovakia to foster networking among progressive activists and politicians across the Eastern European region.

Overall, it has become clear to us that such a program for aspiring progressive politicians is highly needed — and its impact will grow with every new cohort. It was encouraging to observe such a diverse group of dedicated and value-driven individuals discussing the future of our country, which was in sharp contrast to most of our mainstream political spaces. As the impact assessment shows, the program has also reached important improvements in trainees’ skills and confidence. Of course, the long-term impact of the program will only be visible later and this is why alumni activities are crucial.

download this articleKontakt

Kontakt

Kammer für Arbeiter und Angestellte Wien

Abteilung EU & Internationales

Prinz Eugenstraße 20-22

1040 Wien

Telefon: +43 1 50165-0

- erreichbar mit der Linie D -